London,

1914. Calvero (Charles Chaplin), once a great music hall comedian, is now

an alcoholic. Arriving home drunk, he smells gas coming from another apartment

in his boarding house, and breaks down the door. Inside he finds Thereza

(Claire Bloom), a ballerina, lying unconscious. Calvero carries her to

his room and cares for her while she recovers. Thereza, or Terry as she

prefers to be called, discovers she cannot walk. Her doctor tells Calvero

there is nothing physically wrong with Terry and that she is suffering

from hysterical paralysis. Eventually Terry overcomes her paralysis and,

encouraged by Calvero, starts to make her way in the ballet world.

London,

1914. Calvero (Charles Chaplin), once a great music hall comedian, is now

an alcoholic. Arriving home drunk, he smells gas coming from another apartment

in his boarding house, and breaks down the door. Inside he finds Thereza

(Claire Bloom), a ballerina, lying unconscious. Calvero carries her to

his room and cares for her while she recovers. Thereza, or Terry as she

prefers to be called, discovers she cannot walk. Her doctor tells Calvero

there is nothing physically wrong with Terry and that she is suffering

from hysterical paralysis. Eventually Terry overcomes her paralysis and,

encouraged by Calvero, starts to make her way in the ballet world.

Calvero finds new motivation in his relationship with Terry and attempts

a return to the stage. But he can only get small engagements at which he

is an abject failure. At this point in the story, the tables turn and it

is Terry who has to provide support and encouragement to Calvero. While

she tells him that she loves him, she is really in love with Mr Neville

(Sydney Chaplin), a young composer who is also making his way in the world.

Calvero realises this and abandons Terry. Turning again to drink, Calvero

ends up busking for coins in the street. He again meets Terry, who arranges

for him to be employed as a clown in her ballet. A benefit

concert is arranged for Calvero, but things do not turn out as expected...

The presence of husbands on crutches or in wheelchairs in film noir

(Double Indemnity, Lady from Shanghai) suggests that impotence is somehow

a normal component of the married state

In the War Room, Strangelove (Peter Sellers as, perhaps, Edward Teller

or Wener von Braun) explains that perhaps not all is lost. A nucleus of

human specimens could be kept in our deeper mine shafts. Greenhouses can

grow food, and animals can be bred and slaughtered. And, in order to ensure

that humankind will continue, a ration of "ten females to each male" should

be maintained, with the females being of a "highly stimulating nature,"

and the presence of the Joint Chiefs beuing a necessity. Even DeSadesky

appreciates the idea, and as Turgidson demands that we continue to stockpile

nuclear weapons for when we emerge, DeSadesky walks quietly away -- taking

pictures with a hidden camera. And as Turgidson reaches a climax, demanding

that we must not allow a "mine-shaft gap," Strangelove staggers from his

wheelchair: "I have a plan... Mein Fuhrer! I can WALK!"

And a chorus of atom bomb explosions follows, matching a recording of Vera Lynn singing, "We'll meet again...don't know where, don't know when....But I know we'll meet again some sunny day."

Before the Cold War began, the US and Russia were allies in defeating the threat of world fascism posed by the Nazis. And now that that threat is gone, the two countries threaten to destroy each other and the rest of the world. And who is helping them to design their weapons? Scientists like Dr. Strangelove, who, we can infer, probably also designed weapons for the Nazis. Although in real life German scientists who ended up working for the US and the USSR may not have been very sympathetic to the Nazi cause, Dr. Strangelove obviously was. However, now he has come to the US, changed his name, and is working for the government. The fascist part of him that remains is embodied in his right half, which he is constantly trying to suppress, as his right hand tries to make the fascist salute. His stiff smile and nervous demeanour show that he is trying to suppress this part of himself, often making mistakes such as saying "Mein Fuhrer" instead of "Mr. President."

So here's what's happening in the last scene: The US and Russia have destroyed themselves, and Dr. Strangelove suggests a plan for preserving humanity. His plan is a realization of the Nazi's ideal world. A human breeding stock will be selected to live, while everyone else dies, to form a supreme race. Strict military discipline will be enforced in the caves. After the nuclear holocaust, the fascist ubermensch cave dwellers will rule the world.

Dr. Strangelove represents fascism: not dead, as the men in the war room assume, but merely confined to a wheelchair. When it seems that the cave plan will be adopted, fascism is re-released on the world and Dr. Strangelove can walk again. The last line, "Mein Fuhrer, I can walk!" is his cry of victory, as if he is telling the memory of Hitler that after the Third Reich seemed to have been destroyed, he survived to help develop weapons which would lead to the fall of the US and Russia and to the beginning of the fascist world.

So among many things, the film shows the irony in the fact that the US and Russia, after defeating fascism, built nuclear weapons which represented rule by military force and the possibility of mass holocaust to an even greater extent than the Nazis did.

On the

US campaign trail in 2004, Democratic Vice-Pesidetial John Edwards said

this: ''We will do stem cell research. We will stop juvenile diabetes,

Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and other debilitating diseases. America

just lost a great champion for this cause in Christopher Reeve. People

like Chris Reeve will get out of their wheelchairs and walk again with

stem cell research.''

On the

US campaign trail in 2004, Democratic Vice-Pesidetial John Edwards said

this: ''We will do stem cell research. We will stop juvenile diabetes,

Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and other debilitating diseases. America

just lost a great champion for this cause in Christopher Reeve. People

like Chris Reeve will get out of their wheelchairs and walk again with

stem cell research.''

What was going on here? Overwhelmed by the belief that the election of the Kerry/Edwards ticket was a matter of cosmic truth and justice, Edwards allowed his mouth to get ahead of his mind. He actually suggested that his esteemed running mate, John Kerry, would heal the cripples and raise the dead. It was an absurd thing for any candidate, even for vice president, to say in front of God and everybody.

But Edwards said that. It was his ''Strangelove'' moment.

On the 35th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s classic movie, ''Dr. Strangelove,'' it’s worthwhile to reconsider the final scene of that black comedy about government and war. The director had intended to end the movie with a food fight in the War Room. But as the final scene was being shot, Peter Sellers, playing the dark genius Dr. Strangelove, forgot his lines. At the end, when Strangelove was outlining his plans for the survival of a ''nucleus of civilization'' in mine shafts after the nuclear destruction of the world, he was overwhelmed by the great opportunities for himself and his leader, President Muffly Merkin (also played by Sellers).

So what Sellers did then, ad lib, became the end of the movie. It was such a perfect moment that the actor playing the Russian Ambassador lost his composure and had to suppress a smile on his face, which is visible in the movie. It was a darkly perfect parallel to John Edwards’ ''heal the sick'' stump speech this week.

Dr. Strangelove pushed himself out of his wheelchair and staggered to his feet. His uncontrollable right arm shot out and up in the familiar salute. And he said to his great President, Muffly Merkin:

''Mein Fuhrer, I can valk!'' John Edwards could not have said

it better.

In Bond

film From Russia with Love, lesbian Colonel Rosa Klebb is played

by Lotte Lenya. Her name punningly derives from the popular Soviet phrase

for women's rights, khleb i rozy, which

in turn was a direct Russian translation of the internationally used Labor

slogan bread and roses.

In Bond

film From Russia with Love, lesbian Colonel Rosa Klebb is played

by Lotte Lenya. Her name punningly derives from the popular Soviet phrase

for women's rights, khleb i rozy, which

in turn was a direct Russian translation of the internationally used Labor

slogan bread and roses.

She tracks Bond

to Paris, dressed as a wealthy widow. After failing to kill him with a

gun hidden in a telephone, she tries to poison him with a venom tipped

dart hidden in her shoe but Bond blocks the attack with a chair. She is

then captured by Bond's friend Rene Mathis, of the Deuxième Bureau.

She tracks Bond

to Paris, dressed as a wealthy widow. After failing to kill him with a

gun hidden in a telephone, she tries to poison him with a venom tipped

dart hidden in her shoe but Bond blocks the attack with a chair. She is

then captured by Bond's friend Rene Mathis, of the Deuxième Bureau.

Rosa Klebb

was one of two inspirations (the other being Irma Bunt) for the character

of Frau Farbissina, of the Austin Powers series of films who is a lesbian/bisexual.

Rosa Klebb

was one of two inspirations (the other being Irma Bunt) for the character

of Frau Farbissina, of the Austin Powers series of films who is a lesbian/bisexual.

The shoes are on display at the Imperial War Museum in London.

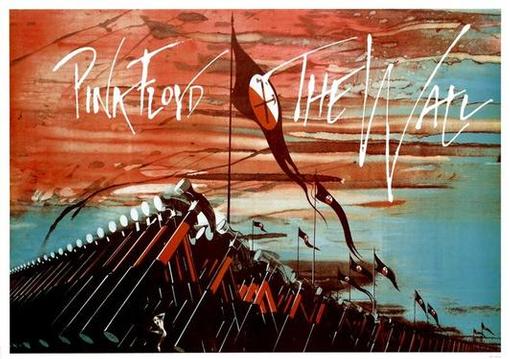

Hammers

are a major dichotomous symbol in "the Wall" possessing both creative and

destructive powers, simultaneously beneficial and oppressive. The same

hammer that constructs a house has the power to tear it down. Similarly,

the hammers in the machines metaphorically create ideal members of society

while destroying each child's individuality. Both natures of the symbolic

hammer are explored in greater detail later in the movie and album as Pink

slips further into his dementia. Furthermore, like the dual nature

ofthe hammers, what begins as a productive revolution (the regaining of

individuality) turns into destructive violence as the children destroy

their school and create a bonfire with the instruments of their past educational

repression that serves as a funeral pyre for their teacher whom they drag

out of the school kicking and screaming. This scene of absolute anarchy

spawned by the overthrow / absence of an authoritarian figure is evocative

of William Golding's novel Lord of the Flies in which a group of school

children

Hammers

are a major dichotomous symbol in "the Wall" possessing both creative and

destructive powers, simultaneously beneficial and oppressive. The same

hammer that constructs a house has the power to tear it down. Similarly,

the hammers in the machines metaphorically create ideal members of society

while destroying each child's individuality. Both natures of the symbolic

hammer are explored in greater detail later in the movie and album as Pink

slips further into his dementia. Furthermore, like the dual nature

ofthe hammers, what begins as a productive revolution (the regaining of

individuality) turns into destructive violence as the children destroy

their school and create a bonfire with the instruments of their past educational

repression that serves as a funeral pyre for their teacher whom they drag

out of the school kicking and screaming. This scene of absolute anarchy

spawned by the overthrow / absence of an authoritarian figure is evocative

of William Golding's novel Lord of the Flies in which a group of school

children  revert

to being savages when their plane crash lands on a deserted island. Similar

to almost every theme in "the Wall," Waters alludes to both the creative

and destructive forces of any one idea. While overly-domineering figures

are destructive to personal development, the absence of any authority figure

is just as caustic. The dictatorial teacher represses each individual child

but the lack of any education whatsoever is just as harmful. In this sense,

living life is like walking a thin wire between two polar but equally destructive

forces; to live, one must either skate over the thin ice carrying the personal

burdens of the past or break through the ice and drown in self-destruction.

revert

to being savages when their plane crash lands on a deserted island. Similar

to almost every theme in "the Wall," Waters alludes to both the creative

and destructive forces of any one idea. While overly-domineering figures

are destructive to personal development, the absence of any authority figure

is just as caustic. The dictatorial teacher represses each individual child

but the lack of any education whatsoever is just as harmful. In this sense,

living life is like walking a thin wire between two polar but equally destructive

forces; to live, one must either skate over the thin ice carrying the personal

burdens of the past or break through the ice and drown in self-destruction.

Animated goose-stepping fascist hammers (Gerald Scarfe) appear in

Waiting For The Worms ("City of fascism"), UK The fascists

are marching. The hammer flags are rising everywhere and Pink is shouting

his orders. Some argue that his work loses some of its nib-scratched, blotching

bite in animated form. Scarfe himself has admitted there were problems

transferring his designs. To begin with, most of the film's animation crew

were more used to drawing 'toons'. And then there were the

restrictions of the production itself - think of the time and cost that

would have been involved in animating each stab of Scarfe's pen! (remember,

this was way before the advent of the cgi techniques we're so familiar

with today...)

'The starting point for this whole project was me feeling bad about

being on stage in a large stadium. There was an

enormous wall between me and the audience - albeit an invisible one - but

one that I felt was there on the basis of the

people I could see in the first 50 or 60 rows; swaying heads - it looked

to

me as if they were experiencing it as well. It's

like when you're singing a very quiet song on an acoustic guitar on stage

and about ten thousand people are shouting and

screaming and whistling, which happened a lot on the 'Animals' tour. There

were at least 20 people that I could see

whistling and going berserk and screaming. They were trying to 'be with

me', if you like, but it doesn't help, you know;

"Whooa-wow-get down", you know, and I'm trying to sing this quiet little

song.

Obviously they [don't understand what I am doing] - the ones who are making

the noise. The problem is that you know

there are thousands of other people who do, and they want to listen to

it. If they were all like that, then OK, you could say,

'Mindless pigs, let's just take the money and run', but you know that there

are people out there who do want to listen to it

and they do understand. The starting point of this project was me thinking,

'wouldn't it be good theatrically to do a show

and to physically construct this wall between me and them during the show

and just cut ourselves off, really antagonise the

audience and let them find out for themselves, how they feel about that.

So in the show we do that - but we don't leave it at

that. In terms of structure of the piece the wall gets finished at the

end of side 2 or, in terms of the show, about half way

through.'

At

the last 80.000 spectators gig of the tour in Montreal,

At

the last 80.000 spectators gig of the tour in Montreal,

Canada on July 6th, 1977 something finally snapped. Roger had been asking

the noisy audience several times to keep

quiet during the quiet songs but it didn't help; they kept on yelling and

screaming and letting off fireworks. He eventually

focussed all of his anger on one guy in the public and at one point in

the show he got so disgusted that he spit that person

right in the face.

Roger: 'A very fascistic thing to do. It frightened me. But I'd known for

a while during that tour - which I hated - that there

was something very wrong. I didn't feel in contact with the audience. They

were no longer people; they had become 'it' - a

beast. I felt this enormous barrier between them and what I was trying

to do. And it had become almost impossible to

clamber over it.'

The show ended with session guitarist Snowy White playing a long and sad

blues as an extra encore to calm the berserk

crowd down. Dave Gilmour had already left the stage. Although nobody could

know it back then, it would be the last real

tour of Pink Floyd in this line-up.

'It's supposed to be about how I think parents start inducing - or

almost injecting -

their own fears into their children from a very early age. Particularly

in my case where they've just been

through a world war or something like that. We all go through devastating

experiences and we tend to pass

them onto our children when they're very young, I suspect.'

It's meant to be about any family where

either parent goes away for whatever reason; whether it's to go and fight

someone or to go work somewhere. In a way it's

about artists leaving home for a long time to go on tour - leaving their

families behind - and maybe coming home dead, or

more dead than alive. This has happened to some.'

Dave Bowman (Keir Dulea) as an old man (?stroke) - note wheelchair

by side of table.

Dorothy looked at him in amazement, and so did the Scarecrow, while Toto barked sharply and made a snap at the tin legs, which hurt his teeth.

"Did you groan?" asked Dorothy.

"Yes," answered the tin man, "I did. I've been groaning for more than a year, and no one has ever heard me before or come to help me."

"What can I do for you?" she inquired softly, for she was moved by the sad voice in which the man spoke.

"Get an oil-can and oil my joints," he answered. "They are rusted so

badly that I cannot move them at all; if I am well oiled I shall soon be

all right again. You will find an oil-can on a shelf

in my cottage."

Dorothy at once ran back to the cottage and found the oil-can, and then she returned and asked anxiously, "Where are your joints?"

"Oil my neck, first," replied the Tin Woodman. So she oiled it, and

as it was quite badly rusted the Scarecrow took hold of the tin head and

moved it gently from side to side until it

worked freely, and then the man could turn it himself.

"Now oil the joints in my arms," he said. And Dorothy oiled them and the Scarecrow bent them carefully until they were quite free from rust and as good as new.

The Tin Woodman gave a sigh of satisfaction and lowered his axe, which he leaned against the tree.

"This is a great comfort," he said. "I have been holding that axe in

the air ever since I rusted, and I'm glad to be able to put it down at

last. Now, if you will oil the joints of my legs, I shall

be all right once more."

So they oiled his legs until he could move them freely; and he thanked

them again and again for his release, for he seemed a very polite creature,

and very grateful.